The narrative of ‘the city divided’ is one that permeates the media, the individual psyche, and municipal politics. In the midst of police violence, social stigma, and economic recession, artists and activists have emerged from the city’s most vulnerable demographic.

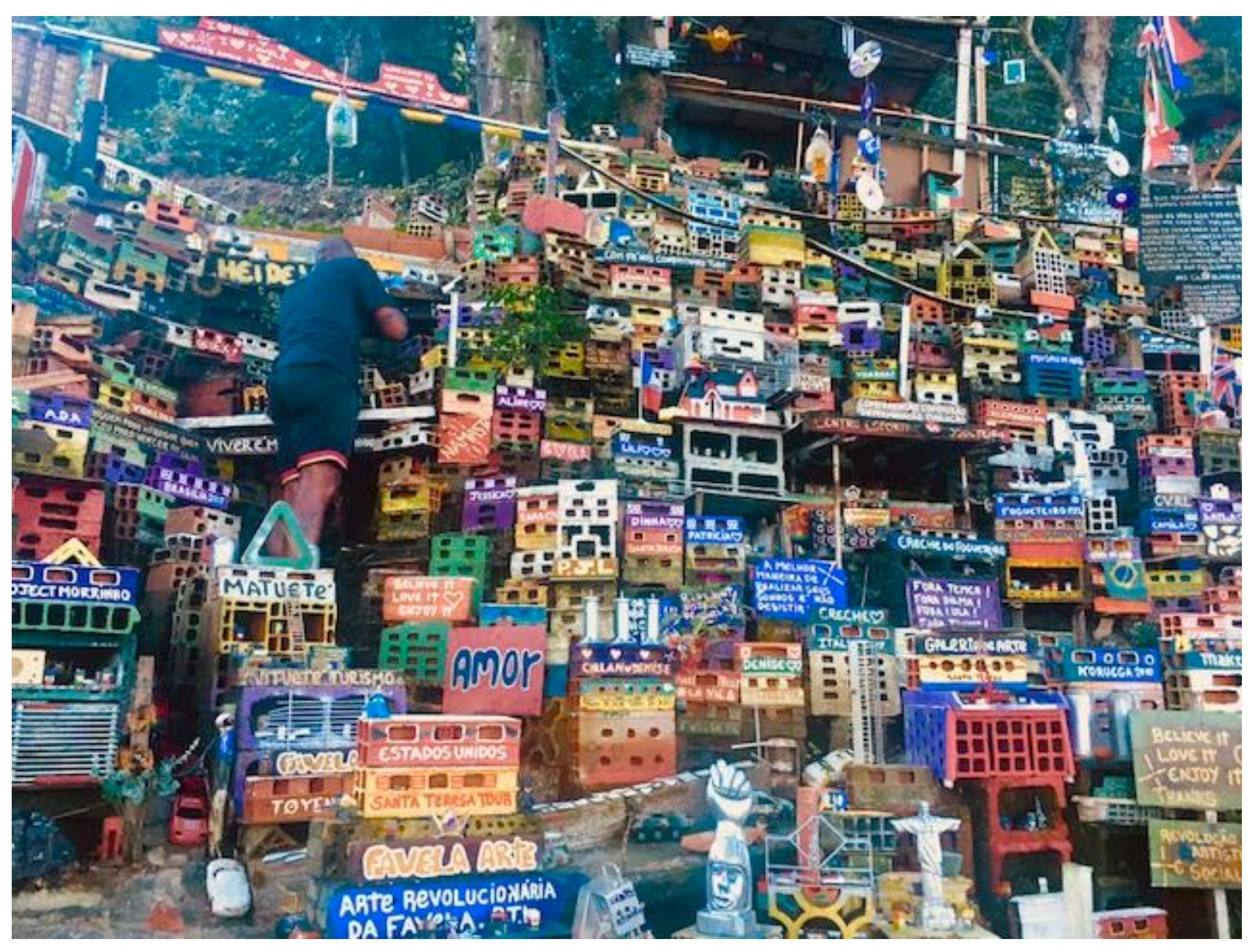

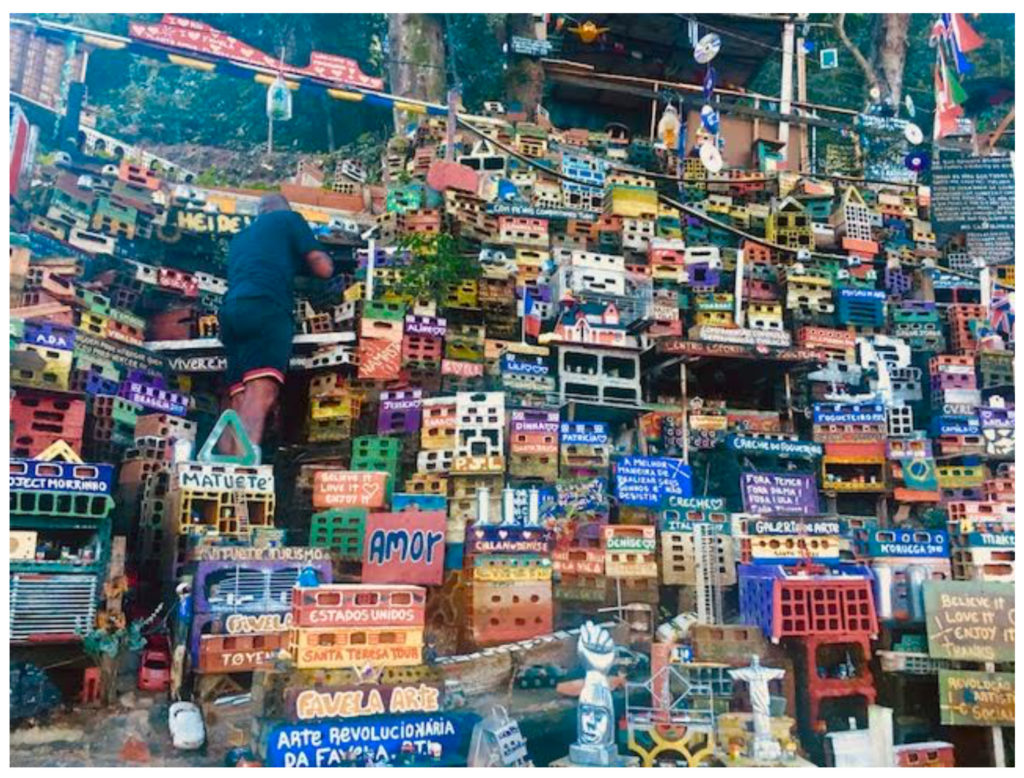

Morrinho has evolved from a creative form of play into an organization with a set of practices that are rooted in the favela and global values of democratization, citizenship, beauty, and identity. The reach of Morrinho is profound. International partners, interested students, visitors, and fellow artists contribute to the establishment of practices that incorporate inclusive values and present and alternative perspective of favelas and the people who live there.

The wide-scale recognition of this artistic, cultural, and social project is well deserved yet there remain barriers to participation within the community that it is embedded. Morrinho, like the favelas, which it mimics in miniature, is vulnerable to the forces of nature and maintaining it is integral to the organization’s mission and meaning. When reflecting on my role as a researcher in Brazil, in Rio, in Morrinho, I would consider myself as an interested novice. My interest in youth-led organization undoubtedly informed what I noticed and what puzzles that I would try to put together about citizenship, activism and art in a country that is new to me. My understanding of Brazilian reality is new, much of it from films and music. I had only a semester of Portuguese language before going to Rio, I knew some basics and was trying to practice as much as I could. Usually Cirlan and Honey would have conversation in English at times but otherwise the conversation was in Portuguese. Denise and I would practice English and Portuguese with each other, which sometimes would end in just using our phones to translate. This proved to be a challenge in my research as much of the literature on the project is in Portuguese. I also think that I missed some of the messages in Morrinho.

What is remarkable about Morrinho is its reach as an organization, whether or not that was ever the intent. The project evolved from a backyard game of sorts to an NGO internationally renowned for its films, community engagement, and youth participation. Morrinho inspires critical thinking and action based on realities of favela life. The story of Morrinho is powerful. It is a story about kids who sought a safe way to be created and to have fun in a space where that was not an easy task. As the boys and girls of Morrinho became women and men, Morrinho became a vehicle for exercising citizenship. The evolution is one that raises a rational and serious debate about the many ways in which people try to create conditions for the fulfillment of human dignity. As long as there remains disjunctions in the experience of being Brazilian or being Carioca, Morrinho’s cause will remain worthy.

Morrinho’s slogan is “a small revolution” which raises an interesting question about its mission. Will Morrinho be able to initiate some sort of massive change in the Brazilian society or Rio de Janeiro? Unequal practices and the treatment of favela residents as unworthy has long been the tradition of the middle and upper classes of Brazil. How can a small model like this create change within a city that remains divided? I have discussed the potential of Morrinho many times with my advisor for this thesis, Christopher London, who often compares this case that I am studying with a change model of agriculture in which he proposes a transformational approach to social change over the typical transitional approach. London’s model “builds on the dialectical claim that the conditions of the future are imminent with the present” (London, 2018). This change model proposes three variations, revolution, liberation, and recapture. In revolution, change occurs as a complete change of the status quo. In the liberation, the change inspires a larger movement which appears as an alternative to the status quo. In the third variation, recapture, where the change becomes a part of society and the norm, this would happen if these grassroots forms of cultural production would then become commodified by the city of Rio. xx Morrinho may not serve as a catalyst for widespread revolution but it fits into a category of new social actors who inspire change. They represent a body of citizens in Rio de Janeiro that are seeking to live with digity and to gain and representation and respect from in politics and in Brazilian society. The art of Morrinho is in one way a spectacle and in a way a space that evolves with the lives of the artists who have complete agency in its design and function. Could this agency be threatened by Morrinho becoming a commodified sight as part of the tourist map of Rio? I am hopeful that Morrinho gains power from the partnerships and exchange of knowledge between the artists and outsiders. Morrinho is a masterpiece so intimately connected to the experiences of those who craft and maintain it that it could not so easily be replicated. Morrinho’s practices are practices of an insurgent citizenship, meant to disrupt the status quo and give voice to those too often silenced.