As the specter of unbridled climate change increasingly weighs on the public’s consciousness, fossil fuel infrastructure has attracted new levels of protest and outrage. For instance, the 2016 Dakota Access Pipeline protests, known by the hashtag #NoDAPL (1). While grassroots advocates, and more recently, ‘big greens’ seek to marshal the public’s newfound momentum against massive, sprawling fossil fuel projects, federal and state agencies responsible for the application, organization and regulation of oil and gas infrastructure remains enigmatic, largely evading the public’s growing ire. Agencies with acronyms like PHMSA, FERC, OEP, OPS, DOT are underestimated for the critical and powerful roles they play in fossil fuel infrastructure development.

For one agency, however, its ‘pre-Trump’ anonymity has come to an abrupt end with several high-profile Trump appointments to lead the agency. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) (2) – is arguably the most decisive of the federal agencies in its administration of the Natural Gas Act (NGA) (3). Since 1938, this federal act has been the guiding regulatory principle to both develop and regulate ‘natural’ gas – which today is almost exclusively extracted via fracking ‘shale plays’ found across the United States.

Pursuant to the NGA, a fossil fuel company must obtain FERC authorization before constructing an interstate natural gas pipeline. Of course there are decisive differences between interstate and intrastate pipelines (4), as well as oil vs gas pipelines – collateral, however, to the unprecedented, rapid investment and construction of pipelines in the last decade carrying various yields of the ‘fracking boom’. Often lost in this rush to transport gas yields across hundreds of miles to both domestic and international markets are people, animals and forests that find themselves caught in a path of toxic impacts.

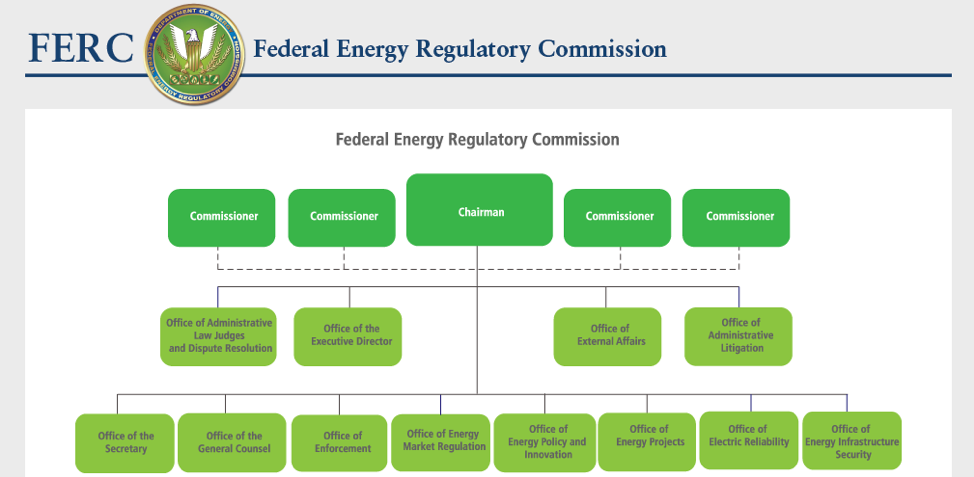

Individuals, families, communities and local governments are given very prescribed roles to play in determining the path of a pipeline. All local decision-making is usurped by the FERC – an authority implicit in the NGA. The FERC makes its certification determinations based on a hierarchy of commissioners, with a second tier devoted to managing litigation and external affairs while consideration of actual environmental and public impacts is buried deep in the bottom of the org chart. This does not bode well for effective public participation.

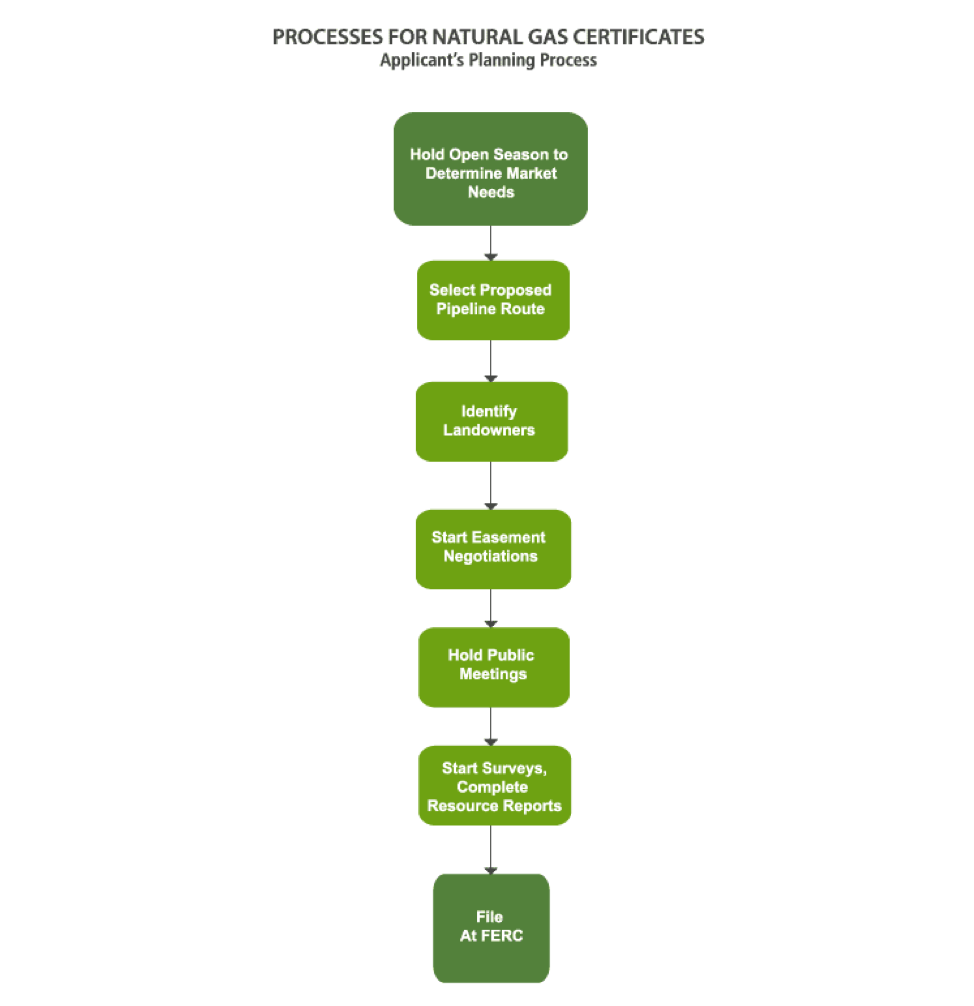

Further, the driving factor in the FERC application process prioritizes ‘market need’ over a public engagement requirement – an often perfunctory and confrontational hurdle that applicants hastily cross on their way to final FERC certification (5). Publicly accessible data and balanced, independent analysis is constrained as applicant-sponsored impact analysis is often hidden behind Privileged and Critical Energy/Electric Infrastructure Information (CEII) clauses. The public rarely glimpses the gritty details of pipeline projects, just their toxic aftermath.

Faced with this disenfranchisement, individuals have very little recourse beyond the provision of ‘timely intervention’ (7) – a filing action on a FERC project docket that establishes that the party (individual, company, governmental body, agency) has valid interest(s) that would be affected by the outcome of a FERC certificate decision. Bureaucratic, tedious and off-putting as it is for public participation, if granted, individuals and community organizations do gain legal standing in the FERC approval process – a critical benchmark for bringing any legal actions against a project.

With the proliferation of pipelines and the local public outrage that they engender, FERC dockets are increasingly marked by numerous individual timely interventions often dramatically outnumbering the law firms and their corporate clients that stand to benefit financially from the granting of a FERC certificate. In a way, the FERC docket becomes an inadvertent Rolodex of a pipeline project – a who’s who of competing interests.

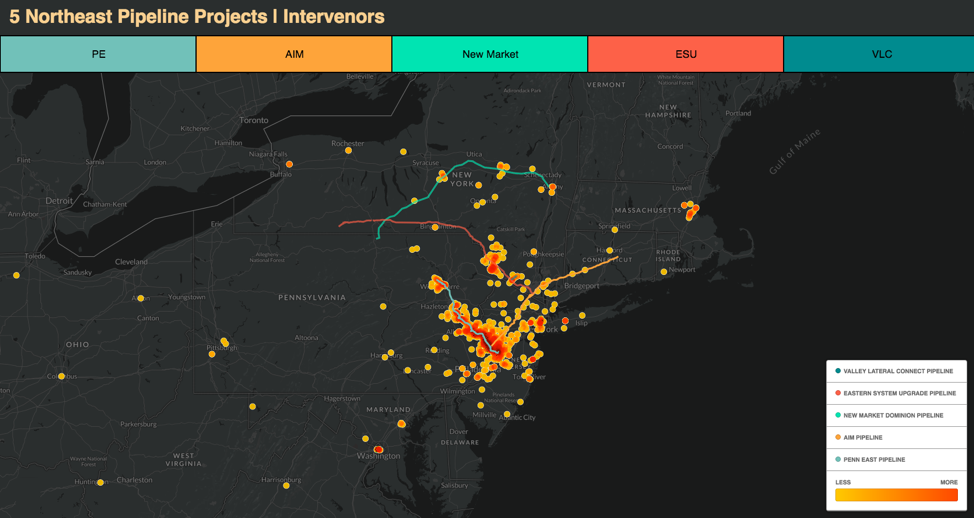

As a precursor to the VzPi project,The Northeast Intervenors Mapping Project, developed during the Fall 2016 semester session of Milano’s Practicum Option, sought to visualize 5 northeast pipeline projects and their intervenors – a tactic to uncover not only pipeline paths but illuminate pockets of activism and community cohesion. The mapping ultimately reinforced the implicit expectation that interests that stand to gain from a pipeline project are inversely proximate to pipeline paths, while individuals with no affiliation or financial interest in the pipeline are highly proximate to its toxic path.

The Northeast Intervenors Mapping Project is both online and interactive, as well as presented and discussed locally with communities fighting fracked gas infrastructure projects. Seeing multiple pipeline battles from a regional perspective helps individuals and their local communities draw important spatial connections with other opposition groups. Further, the map allows local communities to see their ‘strength in numbers’ literally mapped- a powerful reminder that more effective opposition does not happen alone but amongst and through community.

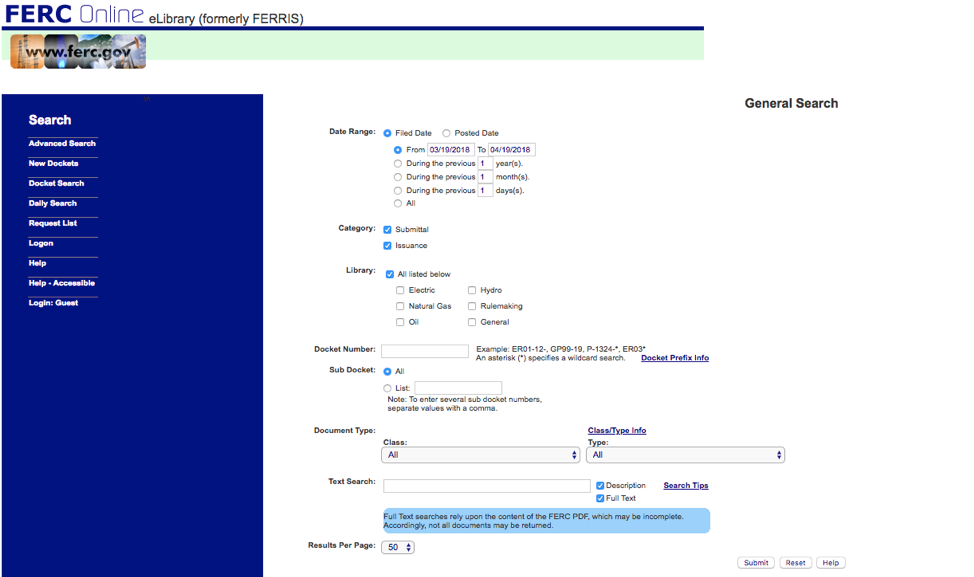

While the visualization of intervenor locational data is highly instructive for community engagement, the data housed at the FERC docket database is a critical source of information for understanding nearly every aspect of a pipeline project – rates, budgets, impact findings, variances, application filings, legal briefs and FERC determinations. However, accessing this data relies on singular search queries on the Ferc eLibrary – a notoriously cumbersome database interface, often offline during weekend hours when the public has time to access the site.

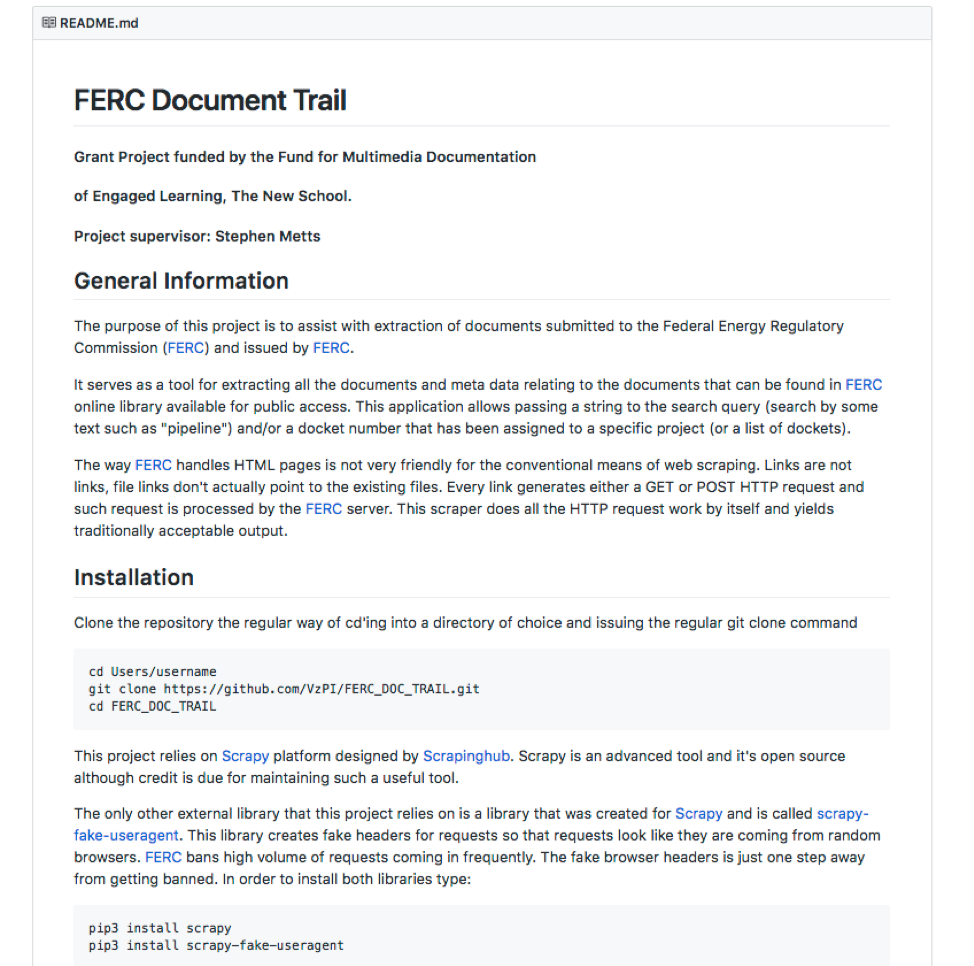

To address shortcomings of the FERC online database interface, Visualizing Pipeline Impacts (VzPI) worked with former New School student Ilya Perepelitsa to develop the Pipeline Impact Scraper [PIS] – a python based project that extracts all the documents and metadata relating to FERC Docket repository for a pipeline project. The tool extracts all publically accessible documents within the FERC eLibrary Docket for a pipeline project; downloads those documents and creates a duplicate, local repository.

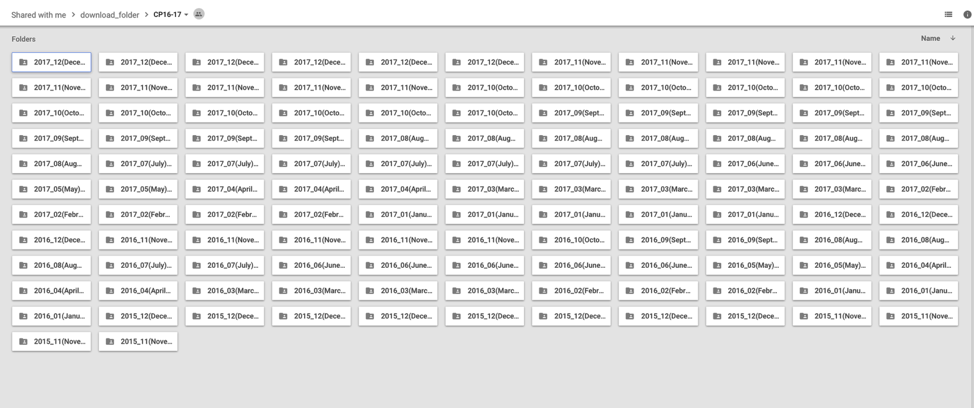

Through the Pipeline Impact Scraper [PIS], not only are all current FERC documents readily available locally, they are organized chronologically into folders, easily searchable. As an open-source project, both the code and python libraries on which the tool runs can be utilized by the public via the project’s github repository for other FERC docket pipeline projects.

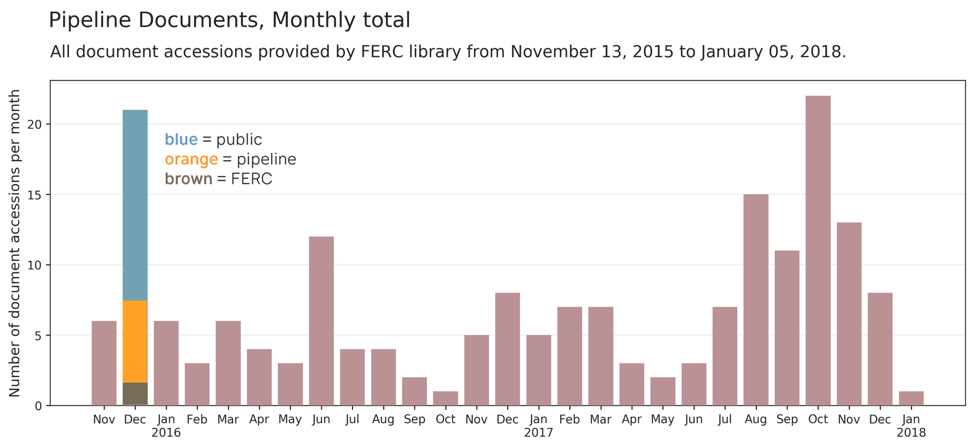

As PIS results are placed into a central repository, a second set of python-based tools are currently under development, tailored specifically to the data structure of the FERC docket. This toolset – Pipeline Impact Visualizer [PIV] – currently visualizes monthly activity in aggregate; further steps are being taken to parse out monthly activity per entity – public commenters, intervenors, the pipeline applicant, state agencies and the FERC. Unlike The Northeast Intervenors Mapping Project that visualizes the spatial dimension of pipeline intervenors, PIV is designed to visualize the temporal dimension of the FERC docket activity to help the public understand the critical role that time plays in the administration of the FERC certification process.

The FERC, like many Federal agencies, is designed to administer and regulate an industry according to highly prescribed legal authority. Its main goal is not to promote better public engagement per se; in fact, increased public engagement is clearly a vexing problem for the agency 8. Through its jargon-filled, docket-centered interface, FERC is off-putting by design. However, with the rapid increase in pipeline approvals through the FERC certificate process, it is inevitable that those in closest proximity to these highly toxic and disruptive projects will become increasingly engaged and vocal in their expectations for transparency and participation in the FERC review process. The VzPi project has developed thorough mapping techniques and the PIS and PIV open-source toolsets, several technical approaches designed to enhance the public’s ability to access and visualize data fundamental to advocating its rights and interests when threatened by a FERC pipeline project.