Solar investors are people or institutions that lend money to solar projects in order to receive tax credits and depreciations credits. In other words, their stake in Community Solar (CS) projects is strictly financial. Learning about the value propositions for investors was quite interesting, as it was very difficult to find investors to speak with or ones that were willing to share information about CS. The lack of first-hand information from investors is a limitation for this case study. There is also dearth of academic literature on the perspectives of investors in CS projects. This study included one interviewee representing the solar investor stakeholder group, but many of the other interviewees from the community and solar developer stakeholder groups shared what they experienced with respect to investors’ value proposition with respect to CS. One key concept that emerged as a value proposition was the desire to mitigate risk as much as possible and to profit from CS projects. As one interviewee said: “Profit is very important; [solar investors] want tax credits, local incentives [and] depreciation benefits [1].”

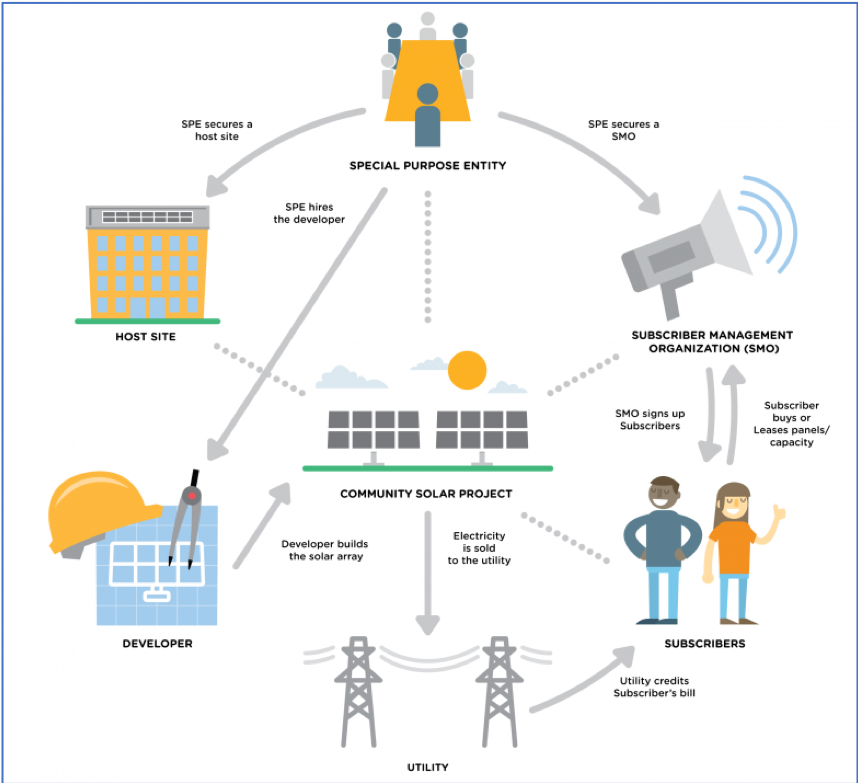

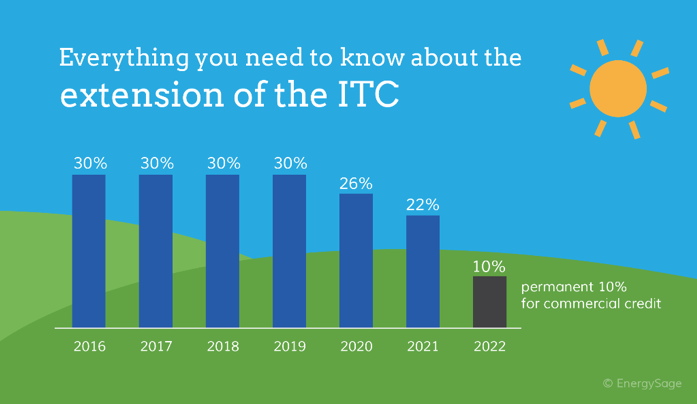

Four out of the ten interviewees mentioned that CS projects offer tax credit benefits to solar investors. In short, solar tax credits, or as they are formally known, federal solar tax credits (also known as investment tax credits [ITC]) allows a solar system owner to annually deduct 30 percent of the installation costs of solar installation from federal taxes [2]. This credit, unless Congress updates it, will decline in value after 2019 [3], so it is in the best interest of community groups to put together projects that are attractive to investors sooner rather than later, which is what the author’s project team will suggest to the community group they are working with. For the team project with the Partner Organization (PO), the team proposed investigating a model where a third party would work with the PO to bring together investors and developers and create a legal entity that can distribute the tax credits to the investors, who would be minority owners of the solar assets. This is known as a special purpose entity (SPE), which would allow the community partner to site and control (to some extent) the CS project within the neighborhood [4]. Since the community partner or PO is a non-profit, they cannot take advantage of the solar tax benefits, but working with a partner that has relationships with investors could be a way that the PO gets CS and the tax credit investors receive the appropriate deductions [5].

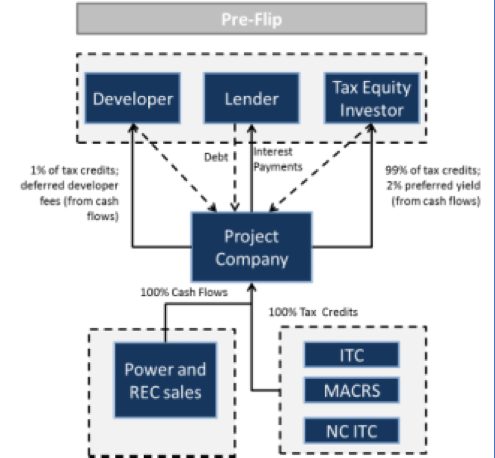

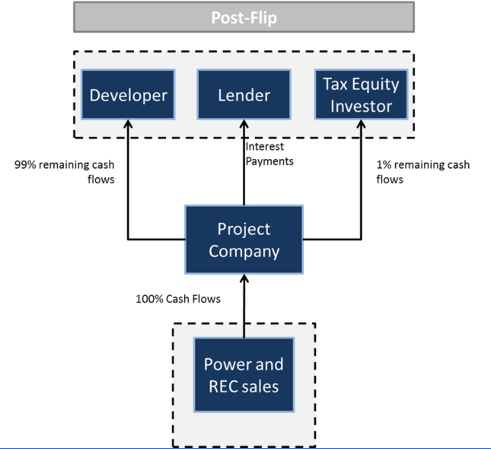

The method of partnership recommended to the PO involves monetizing the tax credits for an investor recommended by the team. This is called a tax equity partnership “flip” model. While this would still involve a SPE, the tax investor would provide 40-60% of the upfront costs of construction for the CS project and then get 99% of the [tax credit] benefits and cash for the next six years [6]. After the sixth year, the ownership of the project would “flip” to the PO.

Additionally, if an investor utilizes depreciation and ITC bonuses, they can get a significant amount of their investment back in less than a year [7]. An interesting side note to this from the interviewee, N.G. is that some tax credit investors may choose to stay invested in a CS project after the debt has been paid off since at that point it would be profitable [8].

The other common theme that investors may be looking for in CS projects (40% or four out of ten interviewees mentioned this) is having an anchor tenant or offtaker. An anchor tenant is someone that would be able to purchase a large amount of power from the CS project. According to the interviewee M.T. (Personal Communication, April 04, 2018) a smaller community organization like the PO “need[s] to mitigate [possibly] unsubscribed energy and partner[ing] with an anchor offtaker for 40-60%…of output” would be beneficial. Again, this is tied to risk mitigation for the CS project. The more stable the project, the higher the likelihood of investors getting their tax credits. M.S. (Personal Communication, April 03, 2018) also agreed with that sentiment, saying that locating anchor tenants will “ease the cost of capital” and “give the project time to develop.” Working with a community group with deep and long-standing ties to the residents and businesses (like the one the author is working with) could, in theory, make the anchor tenant procurement process easier and therefore more attractive to solar investors.

The size of the CS project is also related to project stability and the larger the project, the more solar investors can gain from tax credits. For community solar projects, five interviewees said that 2MW or more is the smallest ideal size. That is a primary reason that the project team suggested that the PO scale up to at least a 2MW system. For investors, this is a way to make sure enough tax credits are generated to make the investment worthwhile. One of the solar installers interviewed, D.C., said that “increasing the system size…spreads out the legal and accounting fess across more investors, as those could be non-trivial for…more complicated community solar projects. [9]” While this would add some extra work for the PO (finding more sites for siting, cultivating relationships with rooftop owners, getting agreements signed for roof access), securing the space for 2 MW would make the project easier to sell to potential investors.

In short, solar investors, are chiefly interested in reducing their tax burden by getting ITC, local incentives and depreciation benefits from investing in solar projects. One investment group that was interviewed said that larger banks would not consider financing even 2MW projects because it would not be worth the risk, but the New York Green Bank may be a possible investor to reach out to for smaller projects in New York state [10]. The more stable and the lower the risk of the solar project, the more attractive it is to potential investors. In a case like this, that means having subscribers for the solar credits, either through individuals or an anchor tenant and at least a 2 MW or larger project size to generate an ample amount of tax credits. There should also be an element of urgency to attract these investors, as the solar ITC value is going to decline starting in the year 2020 [11].

If the PO wants to maximize the value proposition for solar investors, they need to start courting them now to make sure they can ensure the potential investor gets the best benefit.

References:

[1] M.E. Personal Communication. February 05, 2018.

[2] Energy Sage. (n.d.). Why the Solar Tax Credit Extension is a Big Deal in 2018 | EnergySage. Retrieved May 3, 2018, from https://news.energysage.com/congress-extends-the-solar-tax-credit/

[3] Ibid.

[4] Elevate Energy. (n.d.). Three Common Community Solar Business Models. Retrieved May 3, 2018, from https://www.elevateenergy.org/programs/solar-energy/community-solar/business-models/

[5] Ibid.

[6] I.B. Personal Communication. March 22, 2018.

[7] Tax Equity – Solar Capital Finance. (n.d.). Retrieved May 3, 2018, from http://www.solarcapitalfinance.com/tax-equity.html

[8] N.G. Personal Communication. April 27, 2018.

[9] D.C. Personal Communication. February 20, 2018.

[10] C.S. Personal Communication. April 10, 2018.

[11] Energy Sage. (n.d.). Why the Solar Tax Credit Extension is a Big Deal in 2018 | EnergySage. Retrieved May 3, 2018, from https://news.energysage.com/congress-extends-the-solar-tax-credit/