The project is the product of a collaboration with a Brooklyn, New York-based community organization with a focus on environmental justice for low and moderate-income communities of color (for the sake of discretion, names of organizations and individuals will be kept anonymous). Through community discussions on climate justice, the organization decided to investigate the possibility of constructing a 400-kilowatt (kW) parking canopy in the community, to:

- A) offer electricity bill savings to their constituents,

- B) reduce their contribution to carbon-based fuel consumption and

- C) provide visual markers of solar generation in the community.

This case study is focused on exploring the research question: What are the specific value propositions for three stakeholders that are key to building community solar projects: (1) community groups, solar developers and investors. The study provides insight into what is required to develop a community solar project from multiple perspectives. However, the stakeholders in this study are not meant to be exhaustive representations from those three categories. The community groups are not all based in New York and have different aims in their missions, for example. This is the same for the developer and investor perspectives.

There is a significant body of literature about solar policies and studies that have contributed to the progression of Community Solar (CS) or Community Shared Solar (CSS) worldwide. There is also existing literature about different models and discussions on the valuation of solar from multiple perspectives which helps inform this case study.

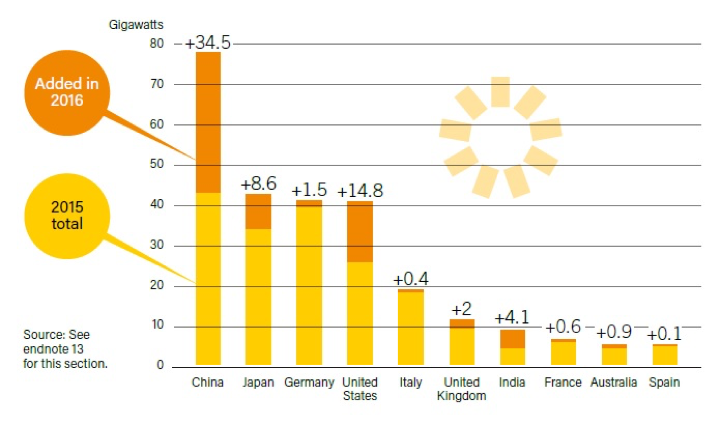

The global solar market, valued at approximately at 28 billion USD [1], is one of the fastest growing sectors in the renewable industry according to the International Energy Agency’s Renewables 2017 report [2]. In fact the report states that in 2016, solar photovoltaic (PV) “grew faster than any other fuel [3]”.

The growing solar market has potential value for multiple stakeholders even in the face of challenges, such as the recent United States’ 30 percent tariff on solar equipment made outside the country [4]. In their 2015 paper, Pitt and Michaud looked at the costs and benefits of distributed solar generation by analyzing studies of the value of solar (VOS) across different sectors, including the utility, government, non-profit, academic and solar industry [5]. This paper was very illustrative of the difficulties in objectively valuing solar, as the values of the commissioners of the studies they analyzed (along with time frame and market considerations) affected the results of the valuation [6]. They also make mention of the capacity of the now-defunct Clean Power Plan’s potential to change the discussion around VOS (as it could have created a national greenhouse gas (GHG) credit market) [7]. Cory and Coughlin (2008), on behalf of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) also looked at how solar financing would be of value to state and local governments back in 2008 and it is apparent that many of the mechanisms put in place then are still relevant today. The report investigated 3rd party ownership, tax credit uses and revenue models that could be used at a (compared to the state) micro level [8].

Community Solar Defined

A community energy project can take many forms. Klein and Coffey (2014) defined it as: “A project or program initiated by a group of people united by a common local geographic location (town level or smaller) and/or a set of common interests; in which some or all of the benefit or costs if the initiative are applied to the same group of people [9].” Since this paper deals only with community solar, a NREL report from 2015 by Feldman et al. argues that CS “encompass[es] approaches to solar deployment that connect community stakeholders to increase the penetration of renewable energy [10].” The same report also illustrates four business (see figure 2) models that can be used to establish a community solar project: community group purchasing, offsite shared solar, onsite shared solar (multi-unit buildings) and community-driven finance models [11].

References:

[1] Eckhouse, B., Martin, C., & Natter, A. (2018, January 22). Trump’s Tariffs on Solar Mark Biggest Blow to Renewables Yet – Bloomberg. Bloomberg. New York.

[2] International Energy Agency. (2017). Renewables 2017 Executive Summary. Retrieved from https://www.iea.org/media/publications/mtrmr/Renewables2017ExecutiveSummary.PDF

[3] Ibid.

[4] Eckhouse, B., Martin, C., & Natter, A. (2018, January 22). Trump’s Tariffs on Solar Mark Biggest Blow to Renewables Yet – Bloomberg. Bloomberg. New York.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid

[8] Cory, K., Coughlin, J., & Coggeshall, C. (2008). Solar Photovoltaic Financing: Deployment on Public Property by State and Local Governments. Golden, CO.

[9] Klein, S. J. W., & Coffey, S. (2016). Building a sustainable energy future, one community at a time. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 60, 867–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.01.129

[10] Feldman, D., Brockway, A. M., Ulrich, E., & Margolis, R. (2015). Shared Solar. Current Landscape, Market Potential, and the Impact of Federal Securities Regulation. Golden, CO.

[11] Ibid.