Please give us your background and tell us about your social practice.

I am traditionally trained as a community and ecosystem ecologist, which means I’m a biophysical scientist first. My path, however, is pretty diverse: from doing science and religion work to teaching quantum physics and cosmology at Columbia University, to helping curate the Hall of Biodiversity at the Museum of Natural History. Coming to The New School was a very important opportunity for me to focus on interdisciplinary science – thinking about how we deal with pressing societal problems by bringing multiple threads of science together as a way of A) understanding the problem; and B) seeing how that understanding can help innovate solutions to problems.

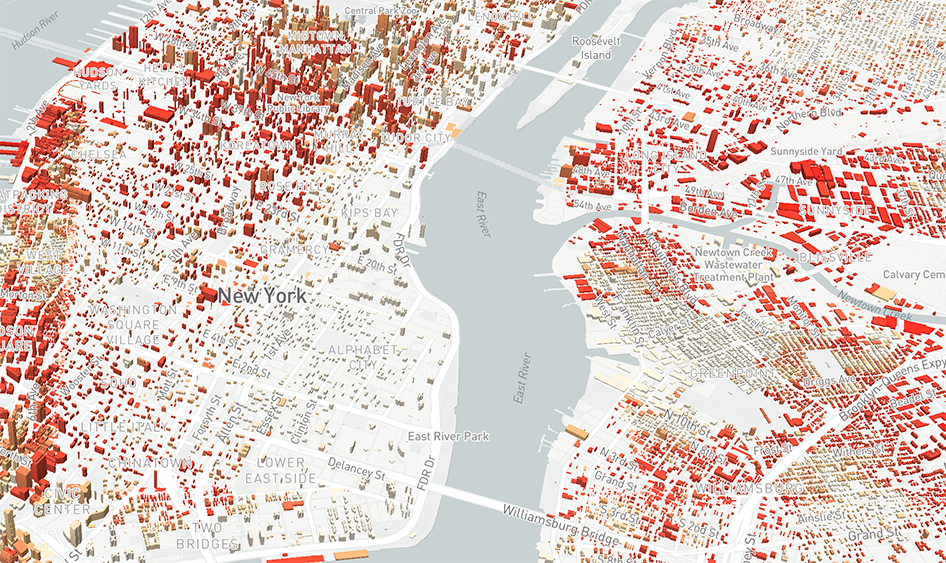

The Urban Systems Lab (USL) grew out of the Urban Ecology Lab I started when I first came the university in 2008, which was then broadened, reframed, and renamed in 2016. Reframing as the Urban Systems Lab was intentional to position the lab around issues that need to be understood from a systems perspective, which frankly, I think are most challenges in the world. If you have a narrow view on whatever that challenge is, whether it is environmental injustice in the inner city, or climate change adaptation in some particular region, it’s nearly always a host of factors that are driving that challenge, that are creating what are sometimes called wicked problems. To my mind, the only way that we are ultimately going to have lasting solutions that don’t fail five years from now is if we take this deeply integrated, systems perspective to both more fully understand both what drives a challenge or problem, and what knowledges, people, institutions, technology, and resources must be brought together to innovate systemic solutions.

In the Urban Systems Lab, we’re trying to address some of the most important problems that we find in urban areas because we see that those are also driving planetary problems. And so, how we improve decision-making – by that I mean policy-making, urban planning, management of different kinds of systems, etc. – by bringing a systems-oriented, interdisciplinary lens to help uncover sustainable solutions that bring long term impacts in cities and beyond.

Can you please tell us more about the socially-engaged scholarship of the Urban Systems Lab?

We’re doing a number of projects with partners, from working with the New York City Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency that was set up post-Hurricane Sandy on stormwater resiliency planning, to work we’re doing around heat vulnerability and heat resilience with the NYC Department of Health and Mental Health, to engaging with local, non-profit neighborhood organizations to develop neighborhood level resilience and sustainability strategies. I have been working in New York City for over a decade and developing relationships here that, together with other colleagues in the USL, are important for doing research that has real-world applicability.

For example, we work closely with the New York City Parks Department, as I have for over a decade now. We’re helping them study ecological dynamics in NYC parks and to think about how we advance the management of our park system so that it benefits more New Yorkers while also bringing ecological and biodiversity perspectives as solutions to social and environmental challenges. How do we improve the performance of urban green space so that it’s absorbing more storm water, so that it’s providing more cooling, as well as recreation, as well as social benefits? These are questions we are seeking to answer to also help prioritize investments by the NYC Department of Environmental Protection.

In terms of thinking of new tools and approaches, we’ve done things like bringing in the role of social media data to understand who uses parks and why do they use them. These are really fundamental questions, but truth is, we don’t know how many people go to our parks, who they are, and why they go there. When you think about something like how do we improve our parks so that they are more equitably accessible and inclusive, so that they provide what people want today in parks, and which might be quite a bit different than what they used to want, we need new assessment and analytical tools. Now we know they want WIFI and other amenities that affect how we manage and plan urban parks of the future. In the USL, we’re bringing new data streams and new ways of thinking more systematically about how you integrate social, technological, and ecological knowledge and data to improve decision-making.

One of the projects I’m really excited about, and I think we’re making some real headway in, is what we call the Urban Resilience project, funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF). It’s a 6-year project to work with 9 US and Latin American cities to advance resiliency to extreme, climate-driven events in urban policy and planning. We’re focusing on: how do we protect the most vulnerable people, and nature, and infrastructure from climate events like we saw in both 2017 and 2018 hurricane seasons in the Caribbean and the U.S.. We’re working in San Juan, Puerto Rico post-Hurricane Maria, and in the New York Region post-Hurricane Sandy. We’re also studying how to improve resiliency to heat waves as well as to flooding from extreme precipitation and coastal storms.

How do you incorporate issues of social justice into your teaching methodology at The New School?

One of the ways I’ve brought social justice into my teaching has been through asking how do we understand who’s vulnerable, where do they live and how can we elevate that understanding in terms of the planning and policy-making that gets done. There is real money being spent around climate change resiliency and we need to target investments in areas where we have vulnerable communities who tend to suffer over and over and over during these climate-driven extreme events. I bring this perspective through readings, class projects, and discussions into my studio and seminar classes.

We know, both historically and in present times, that there’s a pattern where low-income, minorities suffer the most from natural disasters, personally, socially and economically. But there’s a strong focus at the state, federal, and city levels on the suffering of infrastructure. We worry about the economic impacts – and to some extent it’s the loss of jobs and work days – but it’s also about how do we protect our buildings and how do we protect our bridges. What we’ve been trying to do is bring these two discussions, social vulnerability and infrastructure vulnerability, together. We tackle these questions in my Urban Resilience class here at The New School.

We’re also developing a new class on social justice, which will take students into Harlem as our case study taught by postdoc in the lab Elizabeth Cook. But we’re not simply dropping into Harlem to do that. Through funding from the Civic Global Arts program at Eugene Lang College, we’re partnering with WEACT to co-teach part of that class, support our community partners with funding, and embed students in the neighborhood. On the one hand, we’re working with community partners to better understand what are the social justice problems we need to be aware of and how do we link up different communities of practice to address those problems. On the other hand, we’re developing methods to understand and identify where are these vulnerable communities, not just in Harlem, but other areas in the city to build a scientific basis for advocating for investments where people are most in need.

In the NSF Urban Resilience project, which I also bring as a series of case studies in my class, we’ll talk about things that aren’t published, but research that is still in progress, and the students have the chance to give feedback on the scientific approach and methods while it is still in process. I enjoy learning from students in terms of their creative and challenging questions. In our heat resiliency work, for example, we’re looking at where do low-income communities live, where do the elderly live – people who tend to be the most vulnerable in terms of exposure to heat waves and likelihood of morbidity and mortality. For a number of reasons, African Americans in New York City tend to be the most vulnerable population, especially the elderly, and we’re mapping where they live to help gauge the scope of the problem. This is work students take up in class in other cities, to ask similar questions and expand the research through course work.

In the case of our heat vulnerability and resiliency research, we are working directly with the Mayor’s Office to help them think about and make recommendations for where to focus their interventions using analysis developed with students. Is reducing vulnerability about subsidizing air conditioning? Is it about planting trees to cool the neighborhood? Is this about housing retrofits to increase thermal insulation so that there is less solar insolation coming into upper floors through the roof? I bring all of these questions and the research from the many people working in the USL into the class to help students think about the interdependencies of physical housing infrastructure; the nature in which we’ve developed the city so that it produces and traps heat. Then we talk about the historical patterns and legacies of structural racism, which means that certain people, generally people of color and low-income, are living in the housing that is prone to this kind of heat exposure and vulnerability.

The point is, the Urban Systems Lab has been thinking with collaborators about how we take knowledge – local neighborhood knowledge that we’re getting through workshops, interviews and the relationships that we’re building – and how we bring that into the classroom: analyzing, synthesizing and getting feedback and building it into classroom projects. And then how all of this can create a research-practice continuum with decision-making. In some cases, we are serving as knowledge broker between the city and neighborhoods, to try to bring those communities together to improve lives of our residents. We run workshops where we have them both at the table and talk it out – and of course that’s a whole process in itself.

This all looks clean on paper, but it’s messy, difficult work and requires us to learn along the way. It is also a process of bringing students into research experiences where they can get into the messiness of the systems they live in. Whether they’re mapping in GIS with various kinds of data that normally you wouldn’t look at together, or they’re helping us in workshops to sit at tables as the illustrator to help provide design thinking and a design frame for various stakeholders in the workshop, from community residents to various city agencies and nonprofits, students are gaining skills and experience in a variety of skills, techniques, and engagements. On the one hand, students are listening and learning, and on the other, they’re providing a service by bringing the skills they’ve developed at school into that community environment, providing them an opportunity to see their ideas in a visual way.

Can you please speak to the transdisciplinary nature of the Urban Systems Lab’s work?

Transdisciplinarity is central to the mission. It’s always an intersection. Take heavy metals in the soil for example. How is that not a system problem? This is not just soil chemistry, it’s also where did the toxic metals come from and who is being affected? So now it’s social and it’s ecological, but it’s also about the built infrastructure. Is this contamination from lead paint or is it from cars and how do we get it out? That’s what I want students to learn, that you have to look at the larger system to understand the challenge and design solutions. I want students who are going to go out in the world to make a difference. Students need to be able to apply a systems thinking approach about the complexity of the system and not be overwhelmed. Break it down, look at the interdependencies and figure out where is the hinge or the leverage point where we can make change.

Coming back to the Lab, one of the things that we’ve been doing well, and we’re still working on this, is to bring different kinds of expertise together. And so we have social scientists and biophysical scientists, geographers, political ecologists, climate change experts, designers, data visualization technicians, because in the end, we need everyone at the table and they all bring different expertise. It can be overwhelming. It can be exciting. It can be daunting, and rewarding.

I also want to make sure in Urban Systems Lab that we’re thinking about how environmental change intersects with policy being created right now, and how we influence it? For example, the city launched the Cool Neighborhoods program in 2017. It’s a $100 million policy initiative to address heat risk in the city. The New School’s named in there, and we’re cited and recognized as part of the effort to influence that policy direction. And this is something that students have had a hand in and done the analytical work for that’s helped actually drive a policy to decrease heat risk in the city. No policy is perfect and there’s more work to do, but I think it’s a good barometer of how we’re trying to bring various kinds of expertise together to address fundamental challenges in the city.

What are the greatest lessons you’ve learned along the way in this kind of public scholarship practice?

For me, personally, one of the most important lessons has been that I have a lot of learning yet to do. To bring my training and background as a biophysical scientist and what I’ve learned in social science, and then bring all of that into a community setting is challenging. My challenge and greatest learning process is how much skill I have yet to develop in community facilitation. Facilitation training has been really helpful. And I’m still not very good at it to be honest, which is why we have people on our staff who are excellent facilitators and can manage the important political and social dynamics of bringing communities of practice together who speak different languages and have different cultural tendencies.

That’s not something I was ever trained or ever thought I’d be doing in my career. But because we’re actually trying to make a difference, I realized I have to learn this too. I think that’s the challenge of interdisciplinarity and of being a systems scientist: you are going to have to learn how to talk to people who have very different worldviews and very different disciplinary perspectives, in very different walks of life, to bring the needed knowledges together, and that takes practice.